To supplement a 160-milking cow herd and diversify business, Ian Crosbie has ventured into new territory as he breeds animals from the farm’s Holstein herd with Japanese Wagyu to produce snow beef.

With his wife, Nicole, Crosbie helps operate his parents’ farm, Benbie Holsteins in Caronport, Saskatchewan. After first learning about Wagyu beef in a magazine advertisement, Crosbie was immediately intrigued by the breed’s potential. “I started doing a little bit more research on the Wagyu breed. I kind of went down a rabbit hole with YouTube and different social media venues on Instagram and things like that, and became obsessed with this Wagyu breed and the possibility of what we could create out of crossing our Holsteins with Wagyu,” Crosbie says.

They decided to slowly begin to experiment with the Wagyu breed, buying around 30 doses of Wagyu semen from Wagyu Sekai in Puslinch, Ontario. From there, Crosbie says their beef-on-dairy program “snowballed,” leading them to begin marketing their snow beef products in 2018.

Benbie Holsteins now markets their snow beef to high-end restaurants and through a meat distributor which then sells their products to various wholesale and retail buyers throughout Saskatchewan.

A challenge with marketing their products, Crosbie says, has been the regulations restricting the sale of their snow beef outside of the province of Saskatchewan. Benbie Holsteins’ snow beef is not processed in a federally inspected plant, which means it cannot, by law, be sold nationally. Crosbie says sending their cows to a federally inspected plant in Alberta is not realistic for their business at the moment – and currently all their beef is processed nearby in abattoirs inspected by the provincial government.

“There’s lots of other Wagyu-influenced beef brands out there; most of them hail from Australia or the U.S., and they’re allowed to be imported into Canada, yet I can’t export out of my own province,” Crosbie explains his frustrations with the regulations.

Despite these challenges, Crosbie says there is opportunity for dairy producers to succeed in marketing their own beef products. “There’s a lot of different avenues you could go down, whether that be grass-fed or utilizing Angus over Holstein … or just using the natural program or organic. There’s lots of different avenues that could be [taken],” he says.

“The big advantage that we have in the dairy breed is that dairy animals calve year-round, so we always have an inventory of animals. The Holstein cross is a very good one; it marbles extremely well on its own and crosses well with lots of different breeds. It’s a really good base to cross on the beef semen,” Crosbie says.

When deciding which Holsteins to breed with Wagyu sexed semen, Crosbie considers genomics, pedigree and classification. “The goal would be to have the highest-genetic females that we can get off our top holdings, and everything else gets bred to the Wagyu semen for the snow beef program,” Crosbie says.

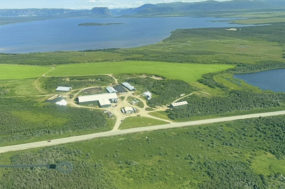

At Benbie Holsteins, snow beef animals are finished on an 11-ingredient ration for a minimum of 300 days. Photo provided by Ian Crosbie.

At Benbie Holsteins, snow beef animals are finished on an 11-ingredient ration for a minimum of 300 days. Photo provided by Ian Crosbie.At Benbie Holsteins, the Holstein crosses and the purebred Holsteins are raised side-by-side, on the same feeding programs until they reach 8 to 10 months old. After that, any animals crossed with Wagyu are put on a background ration for a few more months, at which point they are moved to the finishing pen. In the finishing pen, they are fed an 11-ingredient ration, along with barley silage and oat hay. The animals stay in the finishing pen for a minimum of 300 days, meaning they stay on-farm for about 28 months.

Snow beef is recognized for its high marbling, creating a tender steak which can be sold for a premium. Photo provided by Ian Crosbie.

Snow beef is recognized for its high marbling, creating a tender steak which can be sold for a premium. Photo provided by Ian Crosbie.Wagyu and snow beef are known for their high levels of marbling, which creates a more tender steak, Crosbie says. “The Wagyu breed naturally has a higher level of oleic acid and unsaturated fat in the fat content. So what you get is this fat that will melt at a lower room temperature, and that’s why when people talk about eating Wagyu beef, you’ll get this melt-in-your-mouth quality to it. That’s because the fat content is higher in unsaturated fat and melts at the lower room temperature than your typical North American beef,” Crosbie says.

Crosbie says because of the high marbling, it is quite easy to sell the steaks produced from their snow beef program; however, his profit margins rely on the sale of the lesser meat cuts. He says this is where the ability to have year-round calving is especially beneficial. “It’s not a once-a-year calving season where you have a big slew of beef coming all at once. It’s staggered throughout the year, which makes it a lot easier to be able to market the whole animal,” he says.

Crosbie says he is very happy with the results of his snow beef program thus far. “It’s been a fun adventure; it’s been stressful and exhilarating at times. It’s quite rewarding when you actually see someone or hear someone saying that [our snow beef] was the best beef they’ve ever had,” he says.

In the future, he hopes to see more data generated and released on Holstein beef. “We really need to start pulling some data off for things such as ribeye size, marbling content, the quality of fat in the animal, different average days on feed and different traits that would actually make Holstein beef animals a premium in the marketplace,” Crosbie says. “I think it’s about time, as margins are getting tighter in dairy, that we actually look to utilizing the beef on these animals a little bit more commercially and actually try to grow some value.”