“It is as though milk production and herd fertility are mutually exclusive, and that makes absolutely no sense,” Corless said. “Fertility is the pregnancy rate of the dairy herd; we measure it by herd calving interval and it determines the days in milk. If we understand all three, we have a picture of what is happening with the dairy herd.”

Corless, a ruminant nutritionist specialist for Rumsol Ltd., presented “What if you could break the myth of poor fertility in high-producing dairy cows?” at Alltech’s Global Dairy and Beef Forum in Deauville, France.

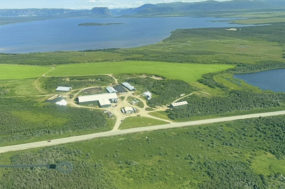

The conference, which welcomed 700 attendees from 43 different countries earlier this year, is held annually and brings together some of the most progressive dairy and beef producers from around the world to enable them to network, share experiences and discuss plans for the year ahead.

“We have a bad habit when we go to farms to only focus on the high-producing group, getting them to peak yields and back in calving, and treating fertility as something separate,” Corless said. “If you want to get maximum profitability and production out of a dairy herd, you need to focus on days in milk and calving interval. By doing that, fertility is now the key component of your profitability.”

In a 2013 study from the United Kingdom, researchers determined the cost of waste in fertility. The UK median calving interval is 423 days while the optimum target is 365 days.

The difference in achieving this goal, due to the percentage of culls for failure to receive and the amount spent on replacements, shows a waste cost per 100 cows at 59,894 euros ($85,722). The cost per cow would be 468.56 euros ($670.62).

“Simply because of poor calving intervals in British dairy herds, they are losing the equivalent in money terms of 1,500 litres of milk,” Corless said. “If they can improve that situation, they will actually get an extra 1,500 litres and an extra 500 euros ($715) per cow per lactation. The objective of a reproductive herd health program is to establish a calving interval that optimizes the production of the herd.”

Optimum calving interval varies between herds. Corless said 365 days is a target rather than a reality. Targeted days in milk should be 170 to 190 and should contain the maximum number of animals in peak yield.

The problem with most dairy fertility rates are that producers tend to only look at the conception rate. Pregnancy rate is measured by conception rates and heat detection rates, and as pregnancy rate increases, more cows will become pregnant sooner.

The heat detection rate and calving rate for first A.I. are the most important factors influencing calving interval.

Corless asked the audience to consider: If heat detection is determined by visual observation, how many people realize that in terms of overtly expressing heat, 70 percent of dairy cows do so far more from 11 p.m. to 9 a.m. while we are asleep?

“Pedometers and ovulation sync programs can improve the heat detection rate, but that doesn’t mean they improve all the people problems,” Corless said. “A 100 percent heat detection rate in first A.I., whether through a sync program or excellent detection skills from employees, can move pregnancy rate from 40 to 54 percent by day 123 and bring down the calving interval up to 15 days. Work that out in cash terms; that is a lot of money.”

According to Corless, the problem is the old adage “If you increase production by 100 litres, you reduce your fertility by a day” that still lingers in the industry. However the notion that when cows get into high levels of production such as 10,000 to 30,000 litres, they are infertile is a myth.

“Management, nutrition, ovulation rate and poor conception on the result of negative energy balance is down to how we manage the animals pre-calving,” Corless said. “It is not a genetic answer. This means there is something we are doing wrong pre-calving in order to maximize dry matter intake post-calving and in order to get these animals back to positive energy balance within 45 days. I see that impact whether that animal is producing 5,000 or 30,000 litres.”

In recent field studies in California herds, using a non-protein nitrogen source and a dietary escape microbial protein during the last three weeks pre-calving and early post-calving, herds have been able to maintain the efficiency rate of microbial protein pre-calving, intakes have remained high in relation to the control, and post-calving the animals have had significant dry matter intake increases.

From a fertility point of view, Corless said he believes it is likely these animals will shift out of negative energy balance quicker, ovulation rates will return sooner, and fertility will increase.

“If you can get them to have higher dry matter intakes, by simple management pre-calving, the negative energy balance period will be significantly shorter,” Corless said. “The micronutrient status pre-calving has a massive impact on metabolic disorders post-calving and improving fertility.”

During post-calving, dairies should also observe the environment or facilities, dry matter intake, nutrition and heat detection. For example, cows walking on concrete are less likely to have overt signs of estrus.

“If a dairy cow after 60 days of good management, whether she is producing 5,000 or 20,000 litres, has overcome metabolic disease impact on conceiving, is no longer in negative energy balance through decent nutrition and management, and continues to repeat, then she is a potential for culling,” Corless said.

“What we see in the majority of herds, the reason our animals are not repeating, is not because of high genetic potential and producing lots of milk, it is simple management and man-made requirements. Pre-calving, heat detection, heat detection rates – are limiting our ability to get these animals back in calving.”

In conclusion, Corless reminded the audience that pregnancy rate relies on both the employees and the management of the animal. By minimizing calving interval, dairies can reach their optimal days in milk.

“Fertility is what gives us milk,” Corless said. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

Ann Hess is the North American field PR manager with Alltech.