The reduction in forage supply and quality over the last six months and the decline in milk prices we are now experiencing are making dairy profitability even harder. With these challenges, the question arises: How can I improve my herd’s feed efficiency to improve the dairy’s profitability?

Feed efficiency has doubled over the last 50 years

In its simplest form, feed efficiency is defined as the amount of milk produced over the amount of feed consumed. However, this does not consider the composition of milk (which determines milk payment) and the energy density of the feed (which is often the limiter of cow performance). To better represent the value of milk components, energy-corrected milk over dry matter intake has been used (i.e., ECM/DMI).

Feed efficiency of dairy cows has doubled over the last 50 years. This increase is largely the result of increasing milk yield, with milk production having increased by 2.5 times per cow thanks to improved genetics and cow management. As cows eat more, a larger proportion of consumed energy goes to production than maintenance. Known as dilution of maintenance, this has been the primary source of improvements in feed efficiency.

Understanding what influences feed efficiency

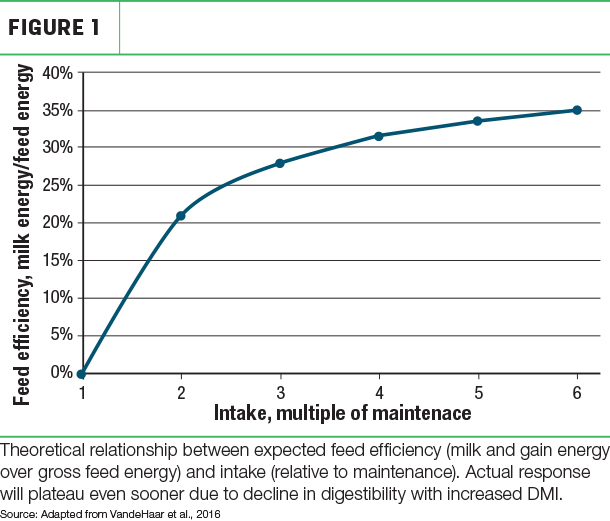

There are limits to increasing milk production to further improve feed efficiency. As DMI of the modern dairy cow increases beyond three times maintenance requirements, the marginal increase in milk production has diminishing effects on feed efficiency (Figure 1).

Given this, two possible routes for further improvements in feed efficiency will be genetic selection for more efficient animals or through nutritional interventions.

The first option is based on the concept that even in the same environment and consuming the same ration, some cows are more efficient than others. In fact, regardless of what multiple of maintenance requirement we look at, there is individual variation across animals. This suggests there is significant opportunity to influence the amount of energy that can be directed toward milk production out of each pound of dry matter (DM) consumed. Of course, the option to advance genetics will take years of research and implementation to further improve feed efficiency.

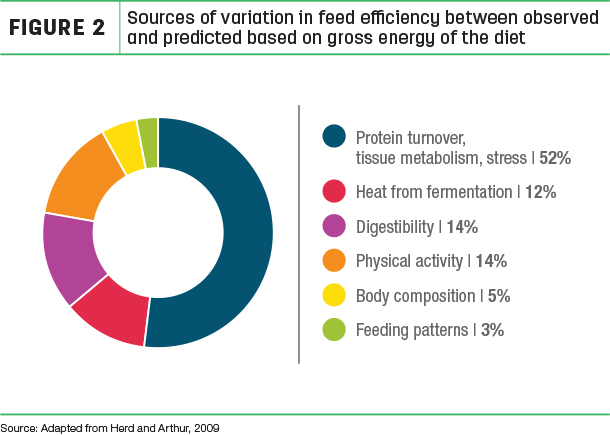

The second option is based on our ability to feed rations that result in more efficient use of energy once consumed. The source of variation in feed efficiency has been associated with six major processes related to the cow: feeding patterns, digestive efficiency, metabolic efficiency, body composition, heat generation and activity level (Figure 2).

About half of this variance could be influenced if a diet is more efficiently fermented in the rumen or if the resulting nutrients are more efficiently used after absorption. Nutritional interventions are attractive for individual farms because they can be adopted quickly for productive and economic gain. Recent research with ammonium lactate provides an example of such an approach that has brought improvements in feed efficiency.

Not all energy is the same

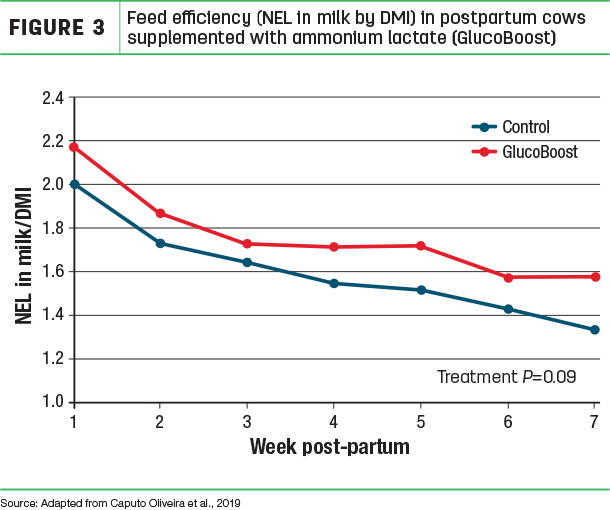

Ammonium lactate is produced through a fermentation process that transforms a byproduct of cheese manufacturing into a high-value feed ingredient. A research study at the University of Wisconsin found when 2 pounds of liquid ammonium lactate (GlucoBoost) per head was substituted for soybean meal to maintain the same level of crude protein in the ration, energy-corrected feed efficiency increased by 10.7% (Figure 3).

This is an impressive response. As milk energy output and body condition were unchanged, the improved feed efficiency came from lower DMI with maintained milk production.

However, energy intake was unchanged, indicating the ammonium lactate was able to compensate for lower DMI by increasing energy supply and utilization (per pound of feed). This additional energy is captured through increased digestive and metabolic efficiency, likely influencing those sources of variation as discussed above. As confirmed in the cow study and in a previous rumen in vitro study at Ohio State University, the ammonium lactate requires minimal rumen metabolism and is fermented to propionate.

University of Wisconsin research has also demonstrated improved metabolic efficiency when feeding ammonium lactate. This was evidenced by increased expression in genes involved in glucose synthesis in the liver, as well as increased glucose in blood. Although not as well understood, feeding liquid ammonium lactate also increased feed nitrogen efficiency, while cows had less blood urea nitrogen.

During in vitro rumen fermentation studies mentioned above, ammonium lactate resulted in reduced methane production by up to 50 percent, suggesting feeding ammonium lactate can reduce energy losses as methane gas. The mechanism and impact of improvements in nitrogen efficiency and decreased methane metabolism should be further examined.

What does improved feed efficiency mean to the farm?

While feed efficiency can seem like a vague concept, when we put feed efficiency in terms of feed saved, we can quickly calculate valuable feed inventory or expenses saved. In the ammonium lactate postpartum supplementation study, improvements in feed efficiency over seven weeks equated to 165 pounds of DM saved per cow. Accounting for the cost of ammonium lactate replacing soybean meal, a resulting income over feed cost was 17 cents saved per day per cow for the ammonium lactate group compared to control.

Another consideration is the forages saved with reduced intake, which may be even more valuable when forage inventory may be limited. Not included in this calculation are the financial benefits of reduced subclinical ketosis also observed during this study.

In summary, there are opportunities to significantly improve feed efficiency by introducing feed ingredients that can improve the metabolic efficiency of cows. This improvement in feed efficiency results in tangible feed and expense savings to the farm. ![]()

Heather White is an associate professor in the department of dairy science at the University of Wisconsin.

-

Michael de Veth

- Vice President of R&D

- Fermented Nutrition

- Email Michael de Veth