Yet somehow, the intake of food combined with time spent in the four stomach compartments allows the dairy cow to produce a nourishing white liquid made primarily of sugar, protein and fat: milk.

It takes appreciation, hands-on experience and training to understand the unique feeding program required by one of nature’s simply designed yet biologically complex domesticated animals.

Enter the dairy nutritionist. Over the years, this group of dedicated professionals has seen significant changes in the industry.

“It’s taken a while for science and technology in the dairy industry to catch up,” says Jakub Bojanovsky, dairy nutritionist with Clearbrook Grain & Milling, a dairy and poultry feed mill and feed supplier based in Abbotsford, British Columbia.

“We used to feed cows in the same way we would feed poultry and swine, but we realized that wasn’t working because of the cow’s complex digestive system.

And we know the type and quality of forage plays a huge role in the cow’s ability to produce milk.”

Bojanovsky, who has several years’ experience working on a dairy farm, holds a bachelor’s degree in animal sciences and a master’s degree in animal nutrition and dietology from the Czech University of Life Sciences.

He’s seen first-hand the changes that have taken place and knows the history behind the evolution of dairy feed.

“Through the years, there’d been this steady increase in how much grain was being fed. More recently, we’ve come to realize that the cow’s ability to produce milk is limited by her ability to consume food. So if you feed a lot of forages, she will only be able to eat a certain amount of food.”

At the most basic level, when you feed a chicken or a pig, what they eat is what they digest. But with a cow, or ruminant, where the food that’s been eaten spends time in the rumen – a name given to the first of the four stomach compartments – the bacteria and microbes in there determine what will be digested.

“Everything the cow eats, the bacteria get a chance to modify, digest or change.”

The challenge for the dairy nutrition industry has been to effectively measure the level of activity inside the rumen and then come up with a nutritional complement to help boost both quality and productivity.

Added to that are consumers’ demands for fewer additives in their food and increased transparency from the food industry. “As a nutritionist, we are constantly striving to balance herd health and productivity while helping to maintain a safe and healthy food chain,” Bojanovsky says.

Decades ago, some products in the dairy nutrition market were intended primarily to boost productivity. Today, dairy nutritionists take more of a holistic approach.

They know the rumen is the key to how everything works, and the idea, Bojanovsky says, is to “add supplements to the rumen to complement what the bacteria in there can’t do.

We look at the dairy cow as part of the ecosystem. She will maximize production while she’s healthy.”

Maintaining overall herd health requires a team effort between the producer, the nutritionist and the veterinarian.

Each respects the others’ skills, insight and areas of expertise because, as Bojanovsky points out, “we’re all working towards the same goal – the health and welfare of each individual cow as well as the overall herd.”

There are other factors to consider besides just nutrition: age, reproduction, injury and disease – even with improved genetics, all of these will, at some point or another, play a role.

The basis for a good feeding regime starts with good grain and forage. Bojanovsky says the first thing his company does with a new customer is take an inventory of what the producer has for forage crops – corn, grass or alfalfa, for example.

Wherever possible, they will try to maximize that usage because if a producer has to go out and buy something, this ultimately affects his or her bottom line.

The importance of good-quality forage can’t be underestimated since this affects not just milk production but also milk quality.

As Bojanovsky puts it, “A dairy cow can only produce milk up to her first limiting nutrient and that will vary depending on diet. Forage is often that first limiting nutrient.”

Making recommendations for ingredients to supplement a dairy cow’s diet can be a challenge. “We bring in ingredients, but cows absorb nutrients,” Bojanovsky says. “While the two are related, it can be difficult for a producer to understand this sometimes.”

Those recommendations are getting easier to make, though, thanks to advances in science and technology. The software that’s available now for diet formulation is impressive, with seemingly endless combinations for different variables, measurements and predictions.

A healthy, lactating dairy cow can consume approximately 22 to 24 kilograms in dry matter per day. Twelve to 14 of those kilograms will come from forage, while the remaining 10 will come from grain mix or supplements.

That grain mix or supplement could be something that a producer supplies on his own but, more often than not, it will be sourced from a feed mill.

Deciding the precise nutritional components of the mix is Bojanovsky’s specialty, but there are other factors to consider. “While having the right nutritional balance is critical, so is the avoidance of contamination with other feeds and external elements.”

“Some producers may think that a feed company can do whatever they want when it comes to the mix, but it’s just not possible. In Canada, we have annual inspections by the CFIA (Canadian Food Inspection Agency) and we’re mandated to track all of our feed and our feed shipments.”

In fact, the protocol for poultry and dairy feed is so stringent that if the CFIA suspects that there has been contamination or errors in shipments, they can shut down a feed mill operation.

When it comes to the mix itself, the ingredients will vary depending on what recommendations the nutritionist has made. Something that’s been getting some added attention lately is the use of enzyme supplements.

The premise is not new, as it’s been used in the poultry and swine industries for decades, but up until now, it’s been difficult to implement in the dairy industry because, as Bojanovsky explains, “the cow’s rumen is full of bacteria, which produce enzymes to break down fibre to make milk.”

He says the concept of adding even small amounts of enzymes took a while to catch on as it was hard to find the right formulation since a lot of the work that was done with enzymes didn’t fit standard enzymology principles.

Technology overall has allowed for significant advances in the entire dairy nutrition industry. “It’s given us so many options,” Bojanovsky says.

“There’s a lot of focus right now on balancing amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein.” It’s been done elsewhere – using specific ingredients in certain ratios for maximum absorption by the cow – but it’s only recently that it’s been applied to amino acids.”

The key factor to keep in mind, he adds, is that this all relates back to that first limiting ingredient. A dairy cow should always have enough energy and protein to maintain health and maximize productivity.

“Once we can predict what’s being delivered to the cow’s intestine, we can take it one step further and predict what the cow will be able to absorb. This allows us to adjust different ingredients to get the right nutrient profile.”

Further adding to that is the fact that, up until now, the dairy industry hasn’t had a rumen-protected amino acid. Bojanovsky explains that feeding two critical proteins – lysine and methionine – has not been possible because the bacteria in the cow’s stomach break down the lysine, rendering it useless.

Research has focused on the rumen-protected amino acid, one that adds a coating which allows it to pass through the rumen so it can be absorbed at the right time.

Dairy nutritionists are also working with crop researchers to maximize diets for dairy herds. “It’s all about what goes into the feed, and what goes into and comes out of the cow, which goes back onto the field, which – over time – will eventually end up going back into the cow.”

It’s taken a while, but science and technology are finally catching up to the unassuming dairy cow, which just goes to show you that you can’t underestimate the simple genius of nature sometimes. PD

—From Clearbrook Grain & Milling

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: Jakub Bojanovsky (right), Clearbrook Grain & Milling dairy nutritionist, meets regularly with customers to determine their ongoing dairy nutrition requirements.

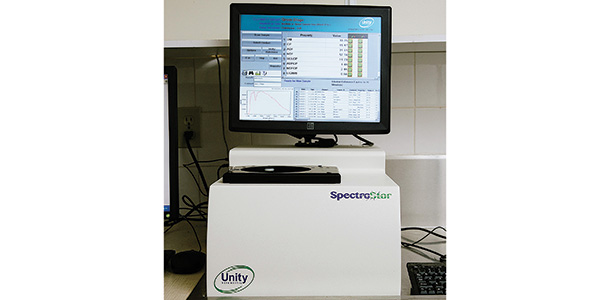

PHOTO 2: Clearbrook Grain & Milling’s in-house NIR (Near-infrared spectroscopy) machine tests feed ingredients to ensure specifications are met and that only those with the highest-quality composition are used. Photo courtesy of Clearbrook Grain & Milling.