As dairy producers can attest, ketosis is a common health challenge. However, without a routine testing program, many producers do not realize how many of their cows are affected. Several large studies indicate that, on average, more than 40 percent of cows experience ketosis at least once during the first two weeks after calving.

Even in very well-managed herds, greater than 15 percent incidence is common.

It’s also an expensive malady. Research at Cornell University published in the March 2015 Journal of Dairy Science shows that the total cost per case of ketosis was estimated at $375 for first-lactation cows and $256 for cows in their second lactation or higher. The average total cost per case of ketosis was $289.

This cost, combined with its frequency and additional negative health and reproductive impacts, makes ketosis a major focus of dairy health management programs.

1. Ketosis defined

The first step in addressing any challenge is to understand what you must deal with.

Ketosis, or hyperketonemia, occurs when blood concentrations of the ketone bodies beta-hydroxybutyric acid (BHBA), acetone and acetoacetate are elevated to the point that undesirable effects are directly or indirectly caused, or are more likely to occur.

It takes two forms – clinical and subclinical ketosis.

Clinical ketosis is the condition with visible signs, including decreased milk production, decreased feed intake, dry manure, rapid loss of body condition and, in exceptionally severe cases, neurological signs such as leaning or walking against the stall front, licking or chewing.

Clinical ketosis may be either primary (meaning it’s the main disease afflicting the cow) or secondary (due to another disease such as displaced abomasum).

Clinical ketosis is, at best, the tip of the iceberg of ketosis in a herd. Often though, recorded clinical ketosis incidence is not a reliable indicator because the diagnostic criteria are not valid or are applied inconsistently. There is no consistent threshold of blood BHBA at which clinical signs of ketosis appear.

According to data from the University of Wisconsin, herds with ketosis problems in early lactation cows also tend to have:

- Increased incidence of displaced abomasum (greater than 8 percent)

- Increased herd removals in the first 60 days in milk

- A higher proportion (greater than 40 percent) of cows with milkfat to true protein percentages below 0.7 at first test after calving

Subclinical ketosis occurs without outward physical signs, but circulating ketone concentrations are above a threshold associated with increased likelihood of undesirable outcomes.

Ketosis is a challenging condition to manage in that the time of diagnosis does not necessarily equate to the onset of the condition. For example, subclinical ketosis commonly precedes displaced abomasum, although they may be diagnosed at the same time.

2. Impact on reproduction

The next step is to determine where the challenge impacts your herd. For instance, depending on the severity and timing of onset, ketosis may reduce milk production in early lactation.

Even more importantly, though, this health disorder is associated with increased risk of endometritis, anovulation, decreased pregnancy at first A.I. and more days to pregnancy. These negative effects extend the impact of ketosis on your herd much longer than you may realize.

Examine your records, and you’ll likely find cows that experienced ketosis during the first two weeks of lactation had reduced probability of pregnancy at the first insemination. In fact, subclinical ketosis during early lactation is associated with:

- 3 times greater odds of metritis (but not always)

- 1.4 times greater odds of endometritis (uterine inflammation based on cytology) at 35 days in milk

- 1.5-fold increased odds of being anovular (not cyclic) at 63 days in milk (19 percent versus 13 percent of cows)

- Decreased pregnancy at first A.I.

Furthermore, cows that had ketosis in one or both of the first two weeks after calving had poorer pregnancy risk until 165 days in milk.

3. Prevention possibilities?

Next, determine how to best prevent the challenge from occurring. In the case of ketosis, your options are rather limited since few management practices or interventions exist that specifically prevent it.

In a large study, only 11 percent of the variation in the incidence of ketosis was explained by readily measured cow-level risk factors (like parity or body condition score).

Therefore, a large part of the controllable variation lies at herd or management level, including:

- Bunk space and feed availability

- Cattle movement and grouping

- Heat abatement

- Feed quality

- TMR consistency

- Water access

- Where approved, use of monensin controlled-release capsules

Based on current understanding of ketosis and its effects, your general objective is to support metabolic health and prevent severe or faulty responses to negative energy balance.

Successfully supporting these factors helps reduce the risk of reproductive disease and impaired reproductive function.

4. Develop testing and treatment protocols

Lastly, develop standards for how you will routinely detect and treat ketosis in your herd.

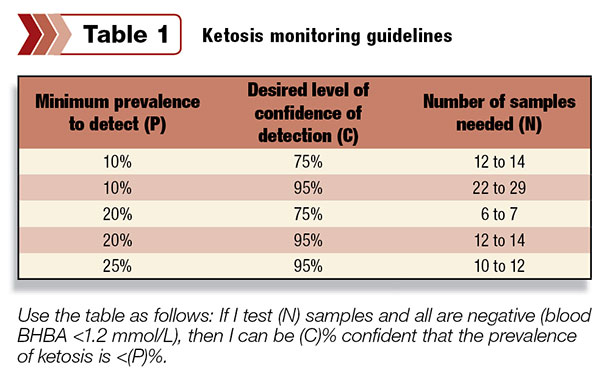

Use Table 1 as a guide for setting up a ketosis surveillance protocol. It shows the sample size for monitoring ketosis in groups of 50 to 1,000 cows in the risk period for ketosis (for example, one to three weeks postpartum).

Use the table as follows:

If I test (N) samples and all are negative (blood BHBA less than 1.2 mmol per liter), then I can be (C) percent confident that the prevalence of ketosis is less than (P) percent.

The number of samples required depends on the prevalence of affected animals you and your team decide it is important to detect, the certainty of detection desired and the size of the group of interest. (This number has the least influence.)

Practically, six is the minimum sample number needed. Twelve to 14 samples will allow for interpretation in most situations. Be sure to take samples at the same time relative to feeding each day to keep results accurate.

Published reports indicate a typical prevalence of subclinical ketosis of approximately 15 percent. Studies in Canada have found average prevalence of 20 percent.

Adjusting for cowside test performance, a threshold of 10 percent true prevalence of subclinical ketosis corresponds to an apparent prevalence (proportion of tests that are positive) of 25 percent when using the Keto-Test milk test strip with a 100 μmol per liter cut-point or 11 percent at the 200 μmol per liter cut-point.

It is misleading to calculate the average BHBA or non-esterified fatty acid from a group of samples and, similarly, most information is lost if samples from multiple animals are pooled together.

Work with your veterinarian regarding ketosis monitoring and treatment protocols that work best for your operation. Be sure to revisit plans periodically, updating them as necessary.

Testing all cows in the first two weeks after calving once weekly is a good starting point. Testing twice weekly will ensure detecting almost all cases.

Meanwhile, based on currently available data:

- Drenching cows with 300 mL of propylene glycol once daily for three days is a reasonable treatment for cows with blood BHBA of 1.2 mmol per liter or greater.

- For cows with blood BHBA greater than 2.4 mmol per liter at diagnosis, treat for five days.

- For all cows, re-test the day after the end of treatment and treat for three more days if BHBA is still greater than 1.2. mmol per liter.

In conclusion, keep in mind that all fresh cows have some ketones in their blood, and all herds have some cows with ketone levels associated with reduced health, production and reproduction. Your objective is to keep the number of cows that fall into these categories as low as possible.

To do so, use a routine monitoring program to reduce incidence and focus on management and nutritional solutions to help optimize metabolic health and immune function while keeping disruptive disorders like ketosis at bay. PD

Stephen LeBlanc is also a professor of ruminant health management and research program director of animal production systems at the University of Guelph, Canada.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Stephen LeBlanc

- President

- Dairy Cattle Reproduction Council

- Email Stephen LeBlanc