Fresh cow metabolic problems are likely the factor with the most devastating effects on milk production and reproductive performance in dairy cattle because a lot of them go unnoticed.

A cow with a difficult calving or retained placenta is expected to have problems, so producers typically treat them assuming they will get ketosis and keep a close eye on them after diagnosis.

However, cows that have a normal calving and transition without any apparent problems are still at risk of developing metabolic diseases such as subclinical ketosis, and if it is not treated on time, it can lead to clinical ketosis, displaced abomasum or even culling.

In the past few years, researchers have shown that farms can vary widely (between 20 and more than 55 percent) in the proportion of fresh cows that suffer subclinical ketosis. To find these, many farms perform monthly Dairy Herd Improvement Association (DHIA) tests that provide information about milk production and milk components for each cow after certain days in milk that vary according to the testing center (somewhere around 7 to 15 days in milk).

It has been long known that the fat-to-protein ratio of the milk can be used as a proxy for the negative energy balance status of the cow, showing a high fat-to-protein ratio when cows are in negative energy balance (subclinical and clinical ketosis).

The major handicap of this test is the cows that are at the highest risk of developing subclinical ketosis (between 3 and 15 days in milk) are commonly not included in the test and are therefore not diagnosed until they become clinical.

To overcome this issue, many producers are setting up monitoring protocols to analyze blood samples for beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA). The problem is determining how often each cow is going to be sampled and at what exact times.

Because of the cost of these tests ($3 to $5 per strip), cows are typically tested only once, targeting the highest risk period between 3 and 15 days in milk. However, this method can miss subclinical animals for multiple days or classify animals as healthy if they are tested before they develop subclinical ketosis.

The only way to monitor the true subclinical ketosis incidence in the herd is through repeated testing of the blood of each cow. This is economically unviable today. However an in-line milk-analyzer system has been developed that tests milk components automatically during the milking of each cow; every milking, every day.

The fat-to-protein ratio measured with this system can be used as a proxy for detection of subclinical ketosis.

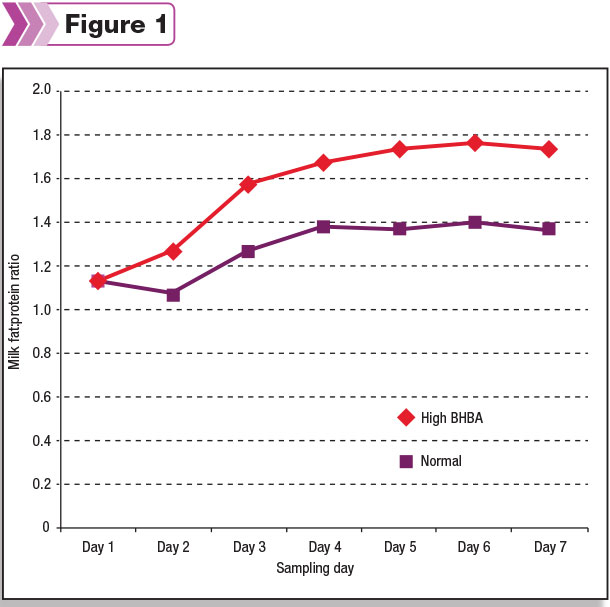

A study conducted at the teaching herd at Oregon State University in 2010 showed that a fat-to-protein ratio of 1.4 was the best cut-off point to identify cows with subclinical ketosis in Holstein cows (Figure 1).

This was based on daily monitoring of cows with the In-Line Milk Lab (AfiLab, Afimilk, Inc., Israel) and comparing its measurements with the BHBA measured from blood samples obtained every day for the first 7 days after calving to determine the presence of subclinical ketosis. In total, 45 Jersey and 45 Holstein cows were enrolled in the study.

Although the cut-off value of 1.4 fat-to-protein ratio was appropriate for Holstein cows, it was not possible to establish a cut-off point for Jersey cows, as their components differ so much from those in Holstein cows. Another study conducted at the teaching herd of the University of Florida using the same equipment showed a cut-off point of 1.42 to identify cows with subclinical ketosis.

One major drawback that farms report when identifying these cows that suffer subclinical ketosis, is that the number of cows treated increases quite dramatically compared to treating only cows with clinical ketosis. However, it has been shown that cows that suffered from subclinical ketosis had a negative impact on milk production of approximately 1,200 pounds per lactation in adult cows and 800 pounds in first-lactation heifers.

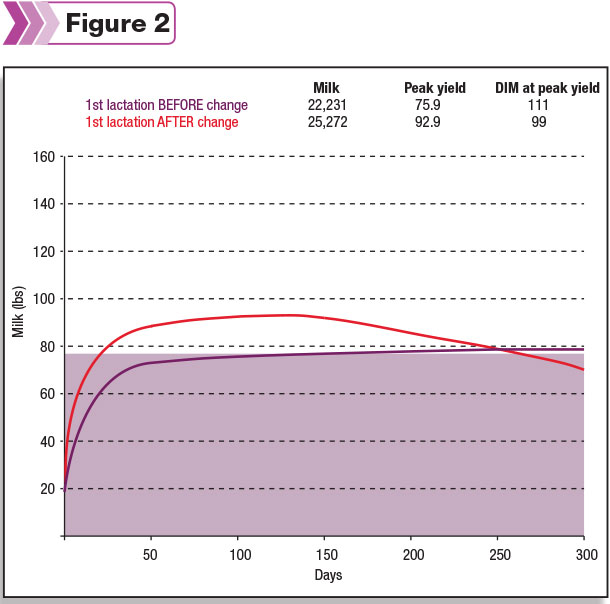

Based on this information, a large commercial farm in the western U.S. milking 4,000 cows and equipped with the in-line milk components analyzer, decided to change from treating clinical ketosis to treat cows diagnosed with subclinical ketosis as soon as they had two consecutive milkings above 1.55 fat-to-protein ratio.

Results are shown in Figure 2 for first-lactation heifers, which produced 3,000 pounds more than those that had been treated based on clinical ketosis signs. The effect on adult cows was less pronounced on this farm, but still significant at 2,000 pounds extra during the entire lactation.

Additionally, this farm saw a decrease in the proportion of animals that were culled from 26.3 to 20.5 percent, and these animals were culled earlier in the lactation, minimizing overall losses.

Additionally, this farm saw a decrease in the proportion of animals that were culled from 26.3 to 20.5 percent, and these animals were culled earlier in the lactation, minimizing overall losses.

Results will depend on the incidence of subclinical and clinical ketosis. A herd with higher incidence will likely see a higher difference compared to a herd with lower incidence. The constant monitoring is able to evaluate changes that impact the incidence of clinical and subclinical ketosis, helping the farm gain better control of the nutritional management of the herd.

One additional advantage observed at the teaching herd at Oregon State University was the diagnosis of severe negative energy imbalances in cows that suffered from coliform mastitis at any point during the lactation. These cows benefited highly from being treated for negative energy balance during the mastitis episode, even late in lactation. PD

Aurora Villarroel grew up on a dairy, has 19 years of experience as a dairy veterinarian and multiple degrees in epidemiology.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Aurora Villarroel

- Applications Support Manager, West

- Afimilk Ltd.

- Email Aurora Villarroel