Finding cows with a locomotion score of “3” could be the magic number that transforms lameness levels within a dairy herd, according to Neil Andrew, Northeast account manager with Zinpro Corporation.

During the 2017 “Don’t Be Lame” workshop series hosted by Cornell University in New York earlier this year, Andrew discussed why identifying moderately lame cows could be the key to turning around one of the most costly problems dairies experience.

Considering the average cost of a lameness case is $400, the payoff of improving this all-too-common ailment is worthwhile from both a financial and animal welfare standpoint.

Identify lameness level with locomotion scoring

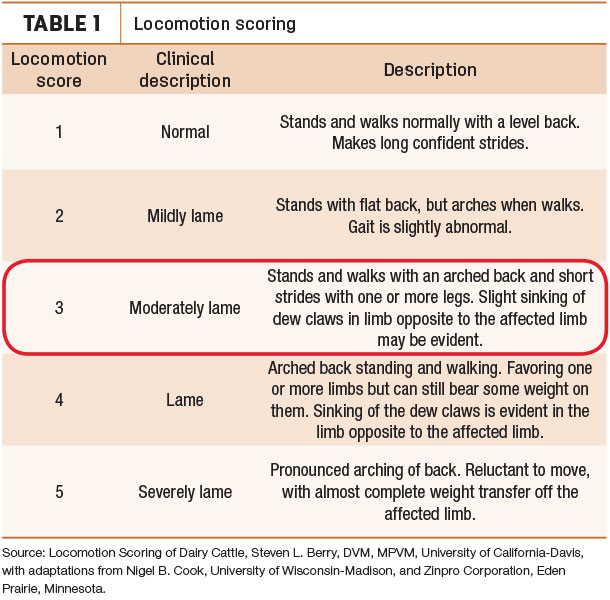

Locomotion scoring serves as a tool to identify lame animals. A trained person observes cows standing and walking (gait), and locomotion scoring assigns a number on a scale of 1 to 5 for each cow based on the level of lameness displayed (see Table 1).

Cows that score 4 or 5 are the obvious, severely lame cows that need prompt treatment, but Andrew believes finding and treating the mildly lame ones is where the greatest opportunity to improve overall herd lameness lies.

“We need to change our mindset to catch cows between a 2 and 3 [locomotion score],” Andrew said, explaining how lameness intervention at this critical point has a higher rate of recovery for the animal and minimizes financial losses for the dairy farmer. “The goal is early intervention,” he added.

Lameness score predicts lost milk

According to Andrew, these scores are a fairly accurate indicator of milk production loss and recovery rate. A locomotion score of 2 correlates with just a 2 percent milk loss, but that number multiplies to 4 percent for cows scored 3, 9 percent for those scored 4 and as much as 15 percent for the severely lame 5’s.

Thus, finding cows that score 3 and intervening before lameness advances to a more severe state can offer significant savings in milk production alone. For a simple example, take a cow producing 100 pounds of milk. If it is just a little bit lame, you’ve lost 2 pounds of milk right there.

As the locomotion score progresses to 3, you are down to 96 pounds. This is the tipping point because as lameness worsens, you stand to lose nearly 10 to 15 pounds of that cow’s milk production potential every day.

In addition to milk loss, cows at a 3 are at a critical point for recovery. With treatment, improvement is likely, but without treatment, the odds of becoming severely lame increase substantially. “If she is a new 3, after one month she is four times more likely to score a 4 or 5 than she is a 2 with no intervention,” he warned.

For instance, a cow with a small sole hemorrhage might score a 3. With prompt treatment, that lesion has a better chance at healing. However, if left untreated, that hemorrhage could turn into a complicated sole ulcer requiring major trimming, blocking and re-check trimming on top of lost productivity.

Lameness also profoundly impacts reproductive efficiency, not necessarily because cows don’t breed back but because it takes much longer. According to Andrew, lame cows have longer days open and are less likely to settle on the first service. Yet one study showed 85 percent of lame cows were pregnant by 480 days post-calving.

These cows were likely still producing well and may not have been lame enough to cull, but the costs related to reproductive efficiency, the animal’s well-being and perpetuating genetics prone to lameness should be considered.

How to find the 3’s

Andrew recommends dairies train a staff person to identify early signs of lameness. Ideally, that person locomotion scores the herd on a weekly basis, observing cows as they move through free-flow areas like exit lanes and breezeways that are part of their normal pattern.

He cautions against assigning this task to the cow pushers for a few reasons. “The pushers usually catch the 4’s and 5’s, the cows in the back of the group they have trouble getting into the parlor,” he said. “The cows that are 2’s and 3’s are in the holding area before the pusher sees them.”

It’s also important to watch cows as they walk at their own pace, without being pushed. Andrew explained that a mildly lame cow being hustled to move will overcome a slight amount of pain, therefore masking her lameness symptoms.

One of the tell-tale signs of a lameness score 3 is the subtle “head bob,” Andrew said. “This tells you the cow is trying to relieve pressure,” he explained.

At this stage, the cow is not yet favoring one foot or showing a pronounced arch to the back; however, the condition could escalate if intervention is delayed until the next visit from the hoof trimmer.

“Every farm should have a way to properly restrain and deal with a lame cow,” Andrew stressed. “They should have the rudimentary skills to alleviate pain until a trained professional can fix it right.”

Such basic skills include the ability to administer pain relief, apply a block or wrap, or to open and drain an abscess. Andrew noted providing a rest area like a bedded pack with soft footing and reduced competition improves healing time.

Locomotion scoring resources and training programs are available through extension and some third-party vendors. It takes only a few hours of classroom time and observation to teach an employee to score cows. Andrew suggested scheduling observation time so every cow is observed once per week.

That may mean the trained person spends a couple of hours each day observing specific pens so all cows are seen, as opposed to spending an entire eight-hour milking shift watching cows walk.

Diligence in evaluating locomotion scores and tending to lame cows is especially important in the coming months, Andrew added. That is because lameness shows up at higher rates in the fall, as a subsequent result of heat stress. Excess standing time and lower rumination can lead to laminitis and other non-infectious hoof issues.

By identifying lameness early and intervening with cows showing subtle signs, the costly consequences of severe lameness like milk production and reproductive losses can be avoided. ![]()

-

Peggy Coffeen

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Peggy Coffeen

5 tips for getting ahead of lameness

- Every farm should have someone qualified to identify cows for lameness and be trained to do something about it until the hoof trimmer gets there. If a cow goes five days severely lame, the chances of recovery are slim.

- Determine causes of lameness. Lameness can be the result of infectious diseases like digital dermatitis, or it can be caused by environmental and management factors that lead to conditions such as sole ulcers and white-line disease. Addressing the correct problem at its root increases the success of prevention methods.

- Routine trimming. All cows should be checked and trimmed by a competent trimmer two to three times each year. Ideal times are at dry-off and 150 to 180 days post-calving.

- Evaluate heifers’ hooves. According to Andrew, digital dermatitis can cause permanent, irreversible damage when left untreated in heifers.

- Keep a bedded pack for lameness recovery. A bedded pack may be more work to manage, but it can help lame cows get back on their feet. Be cautious of bedding materials like chopped straw, stalks or coarse wood chips which are sharp and can cause injury between the toes, thus prolonging recovery from digital dermatitis.