Progressive herds in the industry continued with efforts to support hoof health: organized hoof-trimming programs; frequent footbathing; use of deep, comfortable sand-bedded stalls to optimize rest; installed headlocks at the feedbunk to assist handling and reduce feeding competition at the bunk; and grooved concrete flooring to prevent slipping and injury.

The approach successfully reduced herd lameness rates while milk production increased and fertility improved. Coupled with timed A.I. programs, we have achieved pregnancy rates we only dreamed of 10 years ago. Herds expanded and built larger parlors and bigger barns. Those using sand invested in recycling technology.

A new hoof health challenge: Reverse corkscrew claw

Unexpectedly, this perfect storm of change within our dairy industry created a new hoof health challenge. In the very herds that had lameness under control – where sole ulcers, white-line lesions and digital dermatitis were uncommon findings – we started to see something we hadn’t seen before. At first it was a minor nuisance. Experienced hoof trimmers like Travis Busman in Michigan and Karl Burgi in Wisconsin started to see cows and heifers with corkscrew claws, but this time it was in younger animals and in the inner claw of the rear feet. Because of its location compared to the classic corkscrew deformity of older cows, the condition was referred to as “reverse corkscrew,” but more accurately now we refer to the condition as corkscrew claw syndrome – since it is really a collection of clinical signs.

Corkscrew claw syndrome develops predominantly in younger animals rather than older, mature cows. The condition presents classically with mild corkscrewing of the inner claws of both the front and rear feet. The condition is progressive in herds that are affected, with mild deformities seen in breeding to pregnant-age heifers and obvious deformities in lactating cows through all ages. For most herds, it is a minor inconvenience, requiring an adaptation to routine trimming, but for some herds it is a significant problem.

The worst-affected herds have heifers freshen that are basically unable to perform and must be culled quickly, within the first few weeks after calving. These animals have such severe corkscrewing that the rear inner claw becomes the main weight-bearing claw, with the outer claw barely taking any weight at all. In large herds where these animals must walk long distances at milking time, they wear down their soles and develop toe ulcers that are very difficult to treat because the healthy claw is so underdeveloped.

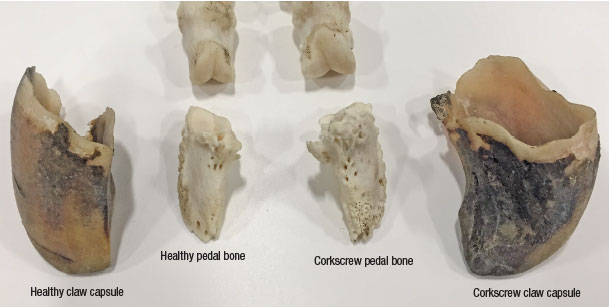

A closer look at these herds will reveal the deformity is common throughout all ages of cows, but it usually starts during the raising period. A closer look in breeding and pregnant heifer pens will reveal a range of animals affected to varying degrees, but the worst-affected are in obvious pain – shifting their weight forward off their hind limbs and sometimes standing with their rear legs crossed to bear more weight on their outer claws. An examination of the skeleton of these heifers after they have been euthanized reveals the source of pain: large, bony scurs on the bones of the foot, suggesting permanent anatomical changes that stay with the animal for its lifetime.

In a recent survey of Wisconsin herds, we found a mean herd prevalence of 16 percent of all heifers affected by the condition, but in some herds more than 50 percent were affected. Holstein, Jersey and Jersey-cross animals have been observed with the condition, suggesting that the solution is unlikely to lie with the geneticists. This is a condition created by the housing environment we have built to raise our replacement animals in.

What’s good for cows is not necessarily good for heifers

We made the reasonable assumption that what was good for our adult cows would be good for our heifers: freestalls, sand bedding, headlocks at the feedbunk and grooved concrete. Initially, we were proved correct, as heifers grew faster and achieved higher milk production. But this combination appears associated with this new syndrome. Coupled with our reproductive performance success on many farms, we are raising too many heifers. Our pens are overstocked, and our animals compete with each other by pushing at the bunk to access feed.

The aggressive flooring, paired with sand bedding, that provides grip and influences growth and wear rates of the hoof horn during development, gives the heifer sufficient surface to exert abnormal forces on the lower limbs. We believe this is what leads to abnormal bone development. Interestingly, however, we have also seen the deformity in mature cows when heifers show few signs. In these herds, they recreate the same problems in the mature cow pens, exacerbated by very high rates of overstocking, sand beds and headlocks with inconsistent bunk management.

It is time to re-think what we are doing. Overstocking all ages of cattle creates problems, and we know now that corkscrew claw syndrome can be added to the list. As much as possible, we need to return to raising heifers on bedded packs and limit freestall exposure to older age groups – preferably after breeding age.

While sand remains great for our adult cows, we need to moderate its use in heifer pens and switch to deep bedding with other materials such as manure solids. Headlocks need to be limited to only those groups that we need to handle frequently, with preference for post-and-rail or slant-bar feeders for the other groups. We also need to re-think our grooving treatments for heifer pens.

As the industry evolves, the problems it faces change with it. We need to recognize the issues and start doing something about them now. ![]()

PHOTO 1: Intensive confinement practices (such as sand bedding, freestalls, headlocks and overcrowding) introduced to heifers at a young age can result in corkscrew claw deformity characterized by the overgrowth and up-turning of the horn. This can occur on either inside claw of the front or rear feet. Photo by Nigel Cook.

PHOTO 2: Reverse corkscrew claw is a painful condition. Examining the skeletal structure of an affected animal reveals the source of pain: large, bony scurs. Compare the healthy pedal bone and claw capsule (left) to the deformed pedal bone from the corkscrewed inner claw (right), which displays symptoms of this condition. Photo by Karl Burgi and Travis Busman.

Nigel Cook is currently chair of the department of medical sciences at the University of Wisconsin – Madison School of Veterinary Medicine and manages the Dairyland Initiative.

-

Nigel B. Cook

- Veterinarian

- UW – Madison School of Veterinary Medicine