On Feb. 22, using Herd Management Score (HMS), Lactanet named the top 25 dairy herds in Canada. To gain an understanding of the financial and herd performance metrics of choice at some of the country’s top-performing dairies, Progressive Dairy contacted the top 10 farms named on the list and asked them to share the business performance measures they regularly monitor.

Here are the answers we received.

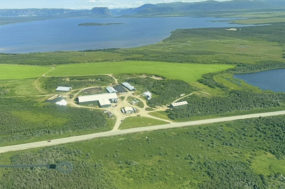

Larenwood Farms Ltd.

The Lactanet Herd Management Score is something we use as a beginning point, and their six metrics are where we begin to measure things. On the reproductive side, we use conception rates and pregnancy rates more than we would calving interval – because calving interval is really only a measure of the cows that are conceiving and when they have a calf again, whereas pregnancy rate is a good measure of those cows that are getting missed and perhaps aren't getting pregnant. So that is one area of reproduction we look at.

We look at milk revenue per cow and what the dollar value is. If that cow is producing, we check that not only does she have milk litres, but also components because we really find a lot about who the herd’s profitable cows are when we monitor components, not just litres.

We aim for a more efficient herd, and we always try to get our herd into that sweet spot in terms of days in milk (DIM). We look at average DIM for the herd and try to keep it within that 150 to 160 DIM range, so we maintain an efficient herd in the high-producing part of their lactations. We are more interested in milking fewer cows to give more milk than milking more cows to produce the same amount of quota. We’re always looking at how we can produce more kilograms of quota for the cows that are in the barn and efficiently using our assets, in terms of facilities and stalls. The fewer cows you have to manage, the easier things are; it helps the cows to be more efficient and to give more milk.

There’s a lot of different metrics you can look at every day, but we try to stick to metrics and information that can easily boil down to this: This is what we can do to improve; this is what we can do to get better.

Estermann Farm Inc.

For us, one thing we look at regularly is our herd benchmarks – which are somewhat similar to the Lactanet Herd Management Score – and we look at our expense ratios; those make up the two main metrics we regularly review. We look at expense ratios quarterly, and the herd benchmarks are something we monitor monthly. Based on our results, we sit down and we see if there are strategic areas where we think we can make improvements.

Heidi Farms Inc.

Return over feed (ROF) is something we track monthly. We feel this is important because feed cost is the largest expense on most dairies. Calculating our ROF monthly allows us to see how changes made to our ration pencil out in actual dollars and cents. It helps us make decisions about which additives and products yield financial results.

We also calculate the cost of production on our homegrown crops on an annual basis. We use these values to make ration decisions and to calculate if it pays to replace any homegrown feeds with purchased byproducts or commodities.

We closely track our transition cow health events, especially ketosis, metritis and milk fever. This helps us catch problems in our transition program early so we can make changes before we are faced with bigger problems.

Ferme Séric Inc.

The measure we look at the most is the calving interval. The reason for this is: We find the more cows calve regularly, the more milk they make, meaning they are bred quickly and, ultimately, produce a lot of milk.

Pfister Dairy Farm

Milk production, components and somatic cell count (SCC) act as our main business performance measures; together, they serve as a key profitability index.

Critically analyzing our DHI results, monthly, on individual cow performance gives us clues in terms of any fine-tuning that must be done to our nutrition, transition cow or heifer program. DHI results also help us determine who our most profitable cows are, who we want offspring from and which are to be sold from the herd. We firmly believe the love our team shares for our herd helps us quickly identify issues and make key management decisions to maintain animal health and well-being. We are most proud of our farm when we maintain a herd of 50% or more three-plus-lactation animals.

While our input costs and income are monitored monthly, we critically analyze our business performance yearly to identify areas of success and areas in which we can reduce our costs.

Lastly, the health of our familial relationships is critical to our business success. We work hard together as a family and constantly communicate successes and failures. Without a strong family and team relationship, our business has no future.

Summitholm Holsteins

To describe what we monitor, we need to break our answer down into two categories:

1. Production benchmarks

At the end of the day, we feel our key efficiency benchmark is kilograms of fat per cow per day. Ultimately, our goal is to fill our quota with the least number of cows possible, and the easiest way to reduce expenses on the farm is to be able to reduce our cow numbers. If we can ship more than 1.8 kilograms of fat per cow out the door, that is a pretty efficient operation.

Other benchmarks we monitor are involuntary cull rate (we aim to keep it at, or below, 17%) along with the lifetime milk production of all milking cows that leave the herd for non-dairy reasons (i.e., cull cows). Ideally, an average lifetime production is 55,000 kilograms. This is a great measurement of career milk for the herd and is interesting to monitor year-over-year.

Another health benchmark we look at is somatic cell count (SCC). We use SCC as one of several culling criteria and as an indicator of parlour function, protocol effectiveness and overall animal stress levels. SCC is more than an udder health indicator; it is a barometer for a lot of different aspects of the farm’s inner workings.

2. Business benchmarks

On our farm, we compare our year-over-year expenses in major categories such as labour, feed, vet supplies and custom operators; however, this information always comes to us well after the financial year is over. We find the clean numbers only come after the tax season, which is three months into the next year. Consequently, we are looking at 2020 compared to 2021, three months into 2022, for example. This is very much a rear-view mirror approach – and something we need to update. As feed is our number one expense, we need to have a more timely and accurate way of measuring it on our farm.

Heerdink Farms Ltd.

One of the metrics we measure is revenue and feed expenses per kilogram of quota and expenses per kilogram of fat shipped. We also look at homegrown and purchased feed expenses per kilogram of fat shipped, in addition to fresh cow events during the first two weeks of freshening. Lastly, we review culling rates and reasons, along with herd inventory, as other measures of farm business performance.

Stewardson Dairy Inc.

Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). That’s the major measure; that’s the one we always go to whenever we do any kind of analysis. For example, when looking at maybe taking on more debt, or to give us a picture of how things are going. We monitor it during quarterly management reviews, so we’ll look at it four times a year.

B. Lehoux et Fils Inc.

Here, reproductive performance takes priority. Keeping an eye on the calving interval, the number of days at the first breeding and the pregnancy rate ensures the cows calve and produce milk. The key is to review the different performance measures daily. How do cows behave today? Have they consumed the ration properly? Is the production level holding? Is the pregnancy rate strong, or why might it not be?

It is important to be attentive to quickly identify changes and adjust as they occur. Like when driving a car, you should not swerve but rather always correct the steering wheel to follow the road.