As the role of dairy veterinarians continues to evolve into a more consultative and proactive approach, dairy vets interested in milk quality and udder health consultation often align themselves with the National Mastitis Council, other milk quality-skilled vets, as well as non-veterinary independent milk quality consultants to enhance their services and deliver a comprehensive, unbiased, cow-based approach to assessing all aspects of milk quality on the farm.

We often get asked to suggest strategies such as vaccine programs and prescribe antibiotic treatment regimes, but to be thorough and make the best recommendations, there is so much more we can do to help assess the whole picture.

1. Record analysis and financial assessment

This is always a good starting point to get a snapshot into how udder health is on the farm. If the herd is on DHI, we can get a lot of information regarding herd linear score and linear score by parity, percentage of new and chronic intramammary infections, as well as the severity of the problem (who, what, when and how well treatment and prevention may or may not be going on the farm).

Dairy vets are also trained to understand the financial impact of diseases and can help farmers understand the costs associated with both clinical and subclinical mastitis. For example, an elevated somatic cell count (SCC) is well researched and documented to be associated with milk production losses. By analyzing records and plugging in current SCC and clinical mastitis rates on the farm into a well-designed spreadsheet, we can assist farmers in predicting the likely financial gains from lowering their herd SCC from 300,000 to 175,000, for example, or lowering their monthly clinical mastitis rate from 8% to 4%.

2. Environmental assessment

Veterinarians can assess cow cleanliness scores, pack or stall dimensions and collect environmental samples, such as bedding, to do bacteria counts on. We can also assess aspects of cow comfort related to ventilation and cow flow.

3. Milk culturing

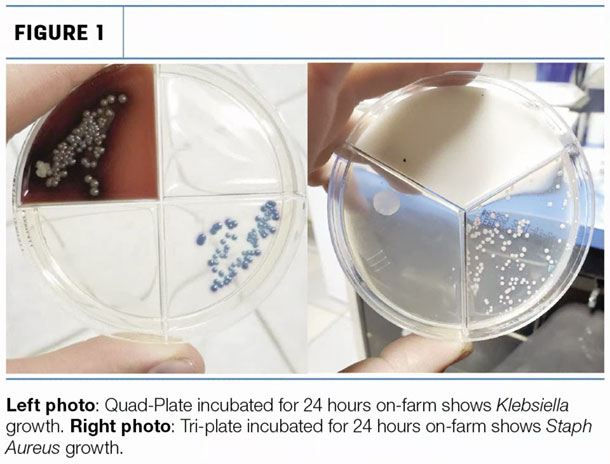

Milk culturing of clinical mastitis cases is often an overlooked but very important aspect of identifying and managing udder health on farms (Figure 1).

If you don’t know what “bugs” you are fighting, it’s hard to know what outcomes to expect and what preventive strategies are the most important to focus on. It is impossible to know what bacteria is responsible for causing mastitis by the clinical symptoms. I often find farms tend to either overtreat or undertreat clinical cases of mastitis (or sometimes both) if they don’t know what they are dealing with.

I sometimes see farms that use the “kitchen sink cocktail” to try and get clinical cases of mastitis to resolve. They start with a few treatments of one intramammary product, followed by another and then maybe another, or might even try two at once. This is problematic since it can create a milk residue or antibiotic resistance concern. If we knew, for example, that the cow had a type of mastitis resistant to treatment in the first place by culturing her milk, we could know that no matter how much or how often we put intramammary tubes into her udder, the mastitis case simply won’t resolve, which will save the farmer a lot of cost and frustration.

4. Protocol development

Once farms start culturing mastitis cases, we are better able to develop treatment protocols. Even better is for farms to move to on-farm or culture-based mastitis therapy. Utilizing this process involves some equipment (incubator and plates) and some training, but this is a great way for farms to quickly identify the bacteria involved in causing the case of mastitis. In turn, vets can design a specific treatment flow chart for producers to follow to make appropriate antibiotic choices, which means cost savings as well more prudent antibiotic use. It also allows us to know which preventive strategies we need to target. There is no point in implementing a klebsiella vaccine program, for example, without confirming that you have a good percentage of clinical cases of mastitis confirmed to be caused by klebsiella.

5. Milking routine assessment

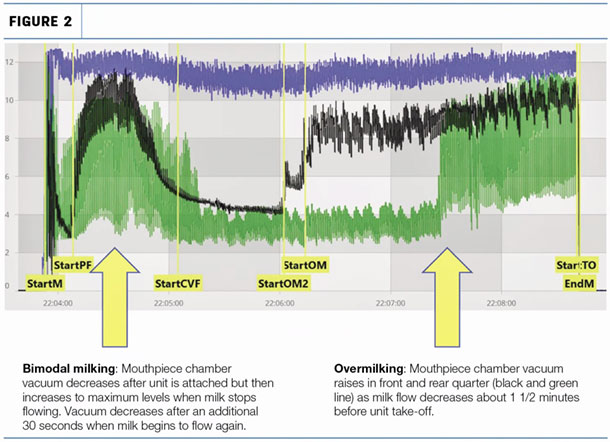

Getting into the parlour and assessing how the cows are milked is a very important aspect of determining the source of any potential udder health concerns. Some of the things we can do in the parlour is assess teat-end scores, look at post-prep cleanliness by doing teat-end swabbing, timing of the prep procedures, post-dip effectiveness and using vacuum recording devices to get an inside look at milk let-downs, overmilking and potential equipment concerns that may be identified under milking load.

Cows themselves are the only ones that can tell us about how they feel about their milking experience, and utilizing devices such as the VaDia give us a window into assessing just that. Allowing cows the appropriate amount of teat stimulation and latency time before unit attachment are common limitations of some milking routines. I have seen producers change only this and, in turn, have seen a dramatic improvement in milking efficiency and udder health.

Robots, although not prone to human-like errors, need to be assessed for how well they are milking cows as well. Attaching vacuum recorders to robots, as well as assessing residual strip volume yields and post-spray or dipping, are important aspects of evaluating robot performance. Teat ends also need to be evaluated routinely to ensure they are in good condition.

Optimizing milk quality and having contented, productive cows is a driving force for veterinarians, as well as for farmers. If the whole picture can be assessed and thoroughly investigated, even small changes can have a significant impact on udder health, milking efficiency and financial gains. ![]()

PHOTO: Mike Dixon.

Dr. Betty-Jo Bradley is a veterinarian based in Picture Butte, Alberta. She is an active member of the National Mastitis Council and has a special interest in consulting on milk quality and udder health. She is a recent graduate of the dairy health management certificate program through the University of Guelph.

-

Betty-Jo Bradley

- Livestock Veterinary Services

- Email Betty-Jo Bradley