Over the last several years working as an environmental consultant on dairies, I have heard one question from my clients over and over again: How do we remove solids from our synthetically lined lagoons? Unfortunately, I have learned that removing manure solids once they have accumulated in a lagoon is easier said than done.

But there are a few tips and tricks to designing and maintaining lagoons that can help you avoid the costly remediation of removing the solids. Since synthetically lined lagoons are becoming more prevalent across the U.S. due to advances in technology and increasing environmental regulations, I hope these lessons learned can save you some money and time down the road.

Here in New Mexico with our stringent ground water regulations, synthetically lined lagoons have become the standard in dairy manure management systems. In New Mexico alone, I have witnessed several different lagoon designs and separation systems currently in operation, each with its own pros and cons, and each with its own lessons learned. As these lagoon systems age, we are finding what is working and what isn't, and have had to develop some innovative and creative solutions to adapt.

When designing a new lagoon, the first thing to think about is solid separation. The most efficient systems have a multistep process to remove manure solids. After the "green water" leaves the barn, pumping it through an inclined screen solids separator can remove a significant amount of the solids. An alternative to an inclined screen solids separator is a weeping wall separator, which passively removes solids using gravity. After passing through the initial separator, further solids separation can be achieved by routing the green water through settling ponds, allowing any remaining solids to settle out. The remaining liquid can then be stored in the final lagoon prior to land application. For a final step, some systems allow for the green water to pass over the mechanical separator one more time before being pumped through the irrigation system. Or, if available, the dairy may have two inclined separators, one for the green water entering the system and one for the green water on its way out to the fields. Removing these solids early on can save you time and money by preventing excess wear on your pumps and preventing manure solids from clogging irrigation lines and nozzles.

Another thing to consider during the designing phase is runoff from storm events. In some systems, runoff is channeled straight into the final lagoon. This runoff can carry debris and other material with it, which ends up in your lagoon if not separated, especially during intense precipitation events. Ideally, runoff should be pumped through the mechanical separator, following the same treatment as green water from the barn. If this is impractical due to large volumes of water, another option is to route the water through a settling chamber prior to entering the final lagoon, minimizing dirt and debris accumulation in your final lagoon from storm water runoff.

When the majority of these lagoons were designed, there was a lack of consideration for future cleaning and maintenance. High-density polyethylene (HDPE) liners can be very slick and can tear easily, so backing equipment down the sides for cleaning and maintenance poses risks. Something to consider when building the lagoon is the installation of a concrete pad down one side or corner, almost like a boat ramp. This ramp provides an access point into the lagoon for equipment. This can make ongoing maintenance of the lagoon easier.

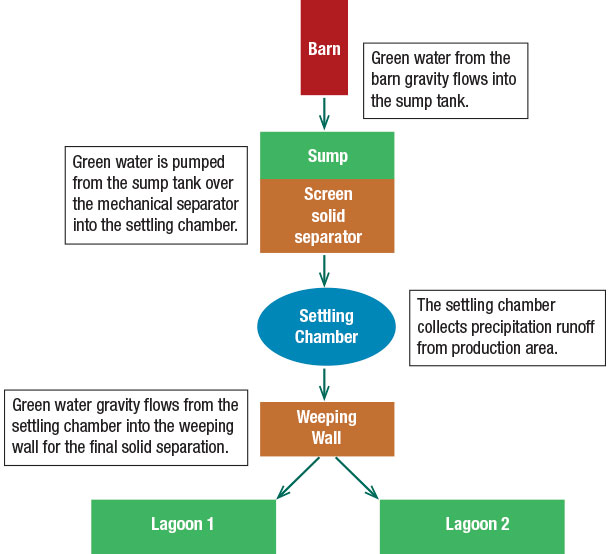

These multistep solids separation processes seem daunting and expensive, but the goal is to save you time and money while giving you peace of mind once the system is up and running. Every facility is different, so finding the right combination of these practices that will work for your facility is key. As an example, one of the dairies I work with has an evaporative lagoon system, but they also recycle water several times to clean the back of the barn, resulting in a large concentration of solids when the green water is pumped to the lagoon system. And with an evaporation lagoon, it is imperative that they minimize solids entering the final lagoon to prevent losing storage capacity. To circumvent these issues, the dairy implemented three different separation components into their green water and manure management system. The green water from the barn is pumped from a sump to a screen solids separator, which then flows into a settling pond. From the settling pond, the green water will flow through a weeping wall into one of two final lagoons for disposal by evaporation. This may sound excessive, but due to the way they manage their dairy, this was the most practical solution.

Routine maintenance can prevent solids from accumulating, and having a plan to remove solids every year or two can prevent a problem before it ever starts. I have seen producers have success with using a honey-vac or similar implements during down times of the year to agitate and pump out solids, but this type of maintenance is time-consuming and can tie up a tractor or trailer. Nevertheless, it can keep solids buildup at bay. Once again, finding what works for your specific facility is important.

There are also a variety of microbial products you can add to your lagoons to help minimize the accumulation of solids. My colleague, Dane Goble at Glorieta Geoscience, explains that these products claim that by inoculating your lagoon with enzymes and microbes on a regular basis, solids are "digested" by microorganisms. As an agronomist, Goble has seen mixed results with these types of products. While it appears they can reduce solids, they can also drastically change the chemistry of your lagoon, specifically the concentrations of plant-available nutrients. This can add some complexity to managing nutrient budgets on fields receiving the green water.

Goble says, "Microbials are great if you can adjust your land application rates to account for increased concentrations of plant-available nutrients. By increasing nutrient concentrations in the lagoon, less green water is needed to meet plant uptake requirements. This can be an issue if you're limited on lagoon capacity and acreage since you won't need to apply as much green water to meet crop needs." When considering these products, be sure to sample your lagoon before and after use to avoid overapplication of nutrients.

When all else fails, there are a few companies you can hire to remove the solids with a floating, remote-controlled, agitator/pump system. At a "small" fee of 1 cent per gallon, you can see how investing in the design upfront and ongoing maintenance can save you money, especially when you are looking at having to remove millions of gallons of solids.

Every dairy and every manure management system is different. I have seen lots of unique systems. In this article, I have included only a couple of different designs. One system that works great for one dairy may not work for a similar dairy down the road. There are limitless manure system designs. Whether you are building from the ground up or making changes to an existing system, do your research and look at the different options. Talk with fellow producers and local consultants to find out what is working and what isn’t. Try and think through the different situations you may encounter on your site and plan ahead for how to handle them. Finding what works for your facility may take some preparing and troubleshooting. Some systems are more complex with digesters and filters, and others stick to the basics. For all dairies, the end goal is the same: successful manure management. ![]()

-

Tara Vander Dussen

- Environmental Scientist

- Glorieta Geoscience

PHOTO 1: Final lagoon with minimal solids.

PHOTO 2: Some solid buildup in the settling chamber is to be expected.

PHOTO 3: Inclined screen solids separator with settling chamber and final lagoon in the background. Photos provided by Tara Vander Dussen.